The Scandinavian countries have long been a priority for Russians in terms of emigration, obtaining a residence permit and establishing long-lasting diasporas. At the same time, the formation of the Russian diaspora in these countries began rather late (except for Finland, which was an autonomous part of the Russian Empire and sheltered many Russian emigrants after the Russian Revolution (1917), especially among the intellectuals). The remaining states of the region, namely Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, stayed outside of Russians and other ex-USSR residents’ interests until the early 1990s. Extensive infrastructure, a high living standard and social benefits prompted fortune-seekers from the former USSR to turn their attention to Scandinavia in the 1990s, although migrants faced competition from Poles and citizens of the Baltic countries.

Recently, events in the countries located in Northern Europe and the Scandinavian Peninsula have been brought up to date due to several activities in which the Russian Federation has a direct interest. These include:

• the regrouping of forces in Europe after Brexit;

• Russia’s implementation of projects aimed at the development of the Arctic and development of Arctic sea routes;

• the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline construction works;

• confrontation about NATO’s attempts on expanding and strengthening in the region;

• the problem of sanctions imposed by European states against the Russian Federation;

• competition in important economic sectors (e.g., energy).

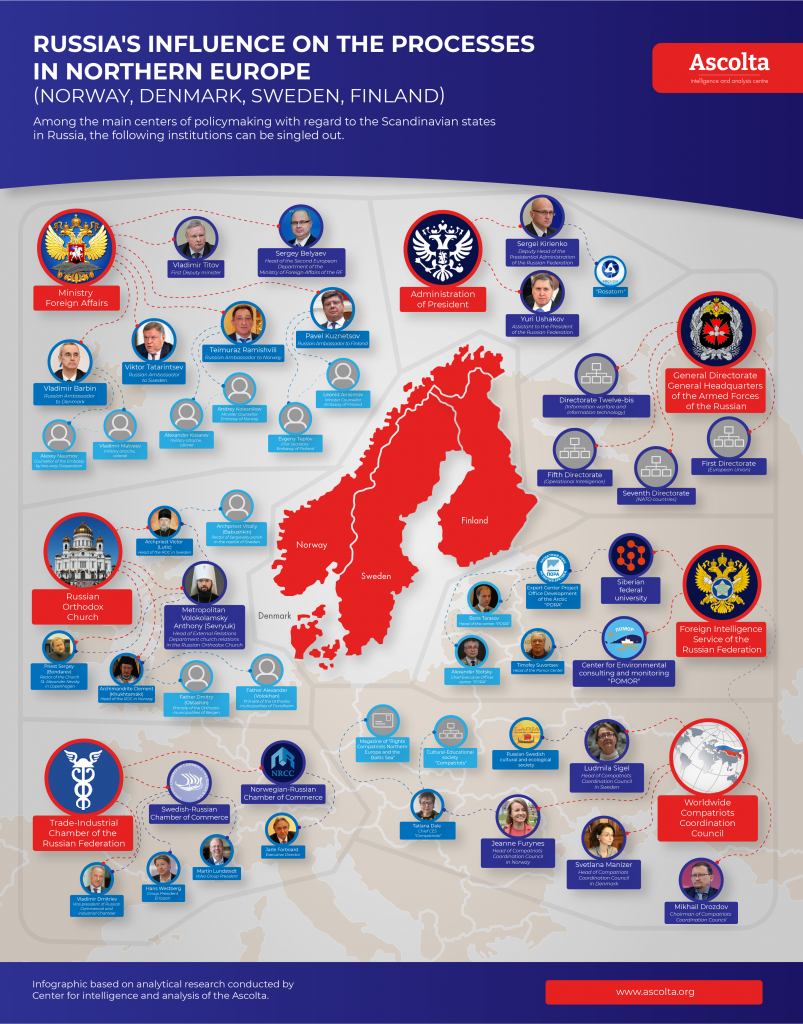

The following institutions are the main centres for the development of policy toward the states of Northern Europe in Russia.

The Presidential Administration of the Russian Federation

The “Northern European” direction is under the personal control of the Assistant to the President of the Russian Federation Yuri Ushakov, who was previously the Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Russian Federation to the Kingdom of Denmark. It is Ushakov who develops recommendations regarding the political line of communication with the states of the region.

In the abovementioned countries, the posts within the embassy also include people who were once proposed by Yuri Ushakov (who is still considered in Russia as the “shadow minister of foreign affairs”).

Also, significant interest in Northern Europe, in particular, in Norway, is shown by the Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration of the Russian Federation Sergey Kiriyenko, who informally keeps his influence in the Rosatom corporation. This corporation has developed and is implementing the Directive for the Development of the Northern Sea Route, which Kiriyenko also takes part in promoting.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation

In the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Scandinavian topics are directly under the jurisdiction of First Deputy Minister Vladimir Titov, who at one time was the Russian Minister-Counselor in Sweden.

Issues related to the Nordic countries are supervised by the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, which has been headed by Sergey Belyaev since October 19, 2018. His negative is that he is a subject matter expert who dealt exclusively with issues of Russian-Finnish relations for a long time and was a minister-counsellor in Finland during 2005-2010 and 2014-2018.

Pavel Kuznetsov took his post as the Ambassador in Finland in August 2017. He is an experienced envoy who started his career back in the days of the USSR. In particular, he worked in Finland during 1980-1985 and 1991-1996, and for some time he headed the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He is fluent in Finnish. Counsellor-envoy Leonid Anisimov and the first secretary of the embassy Yevgeny Teplov are very enthusiastic about their actions.

In Sweden, the Embassy is headed by Viktor Tatarintsev since 2014, who previously served as Ambassador to Iceland and headed the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during 2010-2014.

Since November 2016 Teimuraz Ramishvili performs his duties in Norway (in 2007 – 2012 he served as Ambassador to Denmark). Ramishvili considers himself a member of Ushakov’s team and his student. It is worth mentioning the Ambassador-Counselor of the Embassy Andrei Kolesnikov as an iconic character in the Russian Embassy in Norway, who play an important role in promoting Russia’s interests in the country. So does the military attache Colonel Alexander Kosarev.

In Denmark, the head of the Embassy is Vladimir Barbin (appointed in December 2018), also a member of Ushakov’s team. Previously, he was the Minister-Counsellor of the Russian Federation in Sweden, later he served as the Ambassador-at-Large for International Cooperation in the Arctic of the Russian Foreign Ministry. An important role in the Embassy is played by Military Attache Vladimir Matveev, Minister-Counselor Anna Knyazeva and Advisor for Bilateral Cooperation Alexei Naumov.

The Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation

In the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (GRU), the situation linked to Northern Europe is under the competence of the First (European Union), the Fifth (operational intelligence), the Seventh (NATO countries) and the Twelve-Bis (information warfare and information technology) Directorates.

According to reports, in 2017 the GRU increased the request for preparing specialists in the Norwegian and Danish languages who studies in the Military Institute of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation by three units annually.

The Foreign Intelligence Service

In addition to semi-legal residents, this institution operates through an extensive network of emigrants, diplomats and business representatives. According to public data, Norway is the primary interest in this area. Some projects of the FIS are being developed under the mask of environmental programs. These, for example, include the Expert Center of the Project Office for the Development of the Arctic (PODA), working as a structural unit of the Environmental Fund of the Siberian Federal University (the chairman of the PODA centre is Boris Tarasov, and the executive director is Alexander Stotsky, who previously had a relationship with the activities of the Russian residency in Ukraine).

The Center for Environmental Consulting and Monitoring “Pomor” (Murmansk) also works closely with the FIS. Timofey Surovtsev, the head of the Center, does not hide the fact that his main task is to resist the negative coverage of environmental problems in Russia in the Norwegian media, as well as to establish relations with Norwegian environmentalists (an attempt of holding joint camps in the north of Norway was made in 2018).

The Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church traditionally has an extensive network of representatives in almost all European states. The Department for External Church Relations in the Russian Orthodox Church is headed by Metropolitan Anthony (Sevryuk) of Volokolamsk. Having inherited this post from Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeev), Anthony continues the approach of strict discipline, weekly reports from the clergy on the mood of the congregation and the main tendencies in the social life of the host countries. Since July 2022, serious changes have been made in the structure of the Russian Orthodox Church, including the renewal of primates of foreign churches and parishes.

The jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church in Finland consists of 7 churches, connected in a deanery as part of the Patriarchal parishes of the Moscow Patriarchate.

In Norway, the representative office of the Russian Orthodox Church is headed by Archimandrite Kliment (Hukhtamäki), rector of the Church of St. Equal-to-the-Apostles Olga in the city of Oslo. Vladyka Kliment is 52 years-old ethnic Finn, who was born in a Lutheran family and at a mature age crossed over to Orthodoxy. He is fluent in Russian, English, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian and Greek. According to reports, the leadership of the Foreign Relations Department of the Russian Orthodox Church has a particularly worshipful attitude towards Clement.

The Primate of the Orthodox community of the city of Trondheim, Father Alexander (Volokhan) and the head of the Orthodox community in the city of Bergen, Father Dmitry (Ostashin) are in his compliance.

There is no full-fledged primate of the Russian Orthodox Church in Sweden since 2004. The representative of the Moscow Patriarchate in Finland Viktor (Lyutik) has been appointed as the temporary acting dean of the parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church in Sweden. Archpriest Vitaly (Babushkin), the rector of the St. Sergius parish in the capital of Sweden, deals with the affairs of the church directly in Stockholm. The action plan of the ROC includes the establishment of a Scandinavian exarchate with a centre in Stockholm.

At the same time, several parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia operate in Sweden, which is not under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church. Since the 2000s, the rector of the Alexander Nevsky Church in Copenhagen, Archpriest Sergiy Plekhov, regularly visited the Serbian parish of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Malmö, where he performed church services in Church Slavonic. This resulted in the formation of a local community, which in 2017 began implementing the procedure of state registration of the parish in honour of the Kursk-Root Icon of the Mother of God. In 2018, Priest Ilya Shemyakin, a graduate of the Jordanville Seminary, was ordained for the parish.

In Denmark, the Russian Orthodox Church has a minor presence. In addition to the church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Copenhagen (rector – Father Sergei (Bondarev)), there are churches in Aarhus and Hobro, as well as a convent near Odense.

Chambers of Commerce and Industry

Business associations and chambers of commerce and industry are one of the most effective tools for lobbying Russian interests in Europe.

The Norwegian-Russian Chamber of Commerce (Executive Director – Jarle Forbord) unites about 140 Norwegian and Russian companies. Among its founders are Telenor, StatOil, Orcla Fuds, Acer Querner Contracting, Exportfinance, A-Pressen, the Norwegian Industrial Development Corporation, the State Fund for Industrial and Regional Development, the Norwegian Bank, and a number of Russian companies.

The Russian-Swedish Business Council is headed by Hans Westberg, President of the Ericsson Concern, Martin Lundstedt, President of the Volvo Group, and Vladimir Dmitriev, Vice President of the Russian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. An important point: despite the sanctions against Russia were supported by the Swedish government, not a single Swedish company left the Russian market. The St. Petersburg Economic Forum, which took place in June 2019 was attended by the heads of several Swedish companies – ABB, AstraZeneca, Boule Diagnostics AB, East Capital, EF, Ericsson, Ferronordic Machines AB, Ingka Group (IKEA), Investor AB, Oriflame, Scania AB, SKF, Stena AB, Volvo Group and others.

Non-governmental organisations

Non-governmental organisations play an equally important role in promoting Russian interests in the Scandinavian countries. Among them, there are those directly or indirectly funded by the state, and those grown locally and financed by the diaspora, representatives of local businesses or by other types of donations and contributions.

Among the largest organisations operating in the Scandinavian countries, attention should be pointed to the Worldwide Compatriots Coordination Council (chaired by Mikhail Drozdov). The council was established in 2001. Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke at the Second Congress of the Council in 2002. According to unofficial data, the structure is completely controlled by the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service and Yevgeny Primakov personally was an initiator of its creation.

In Sweden, the Compatriots Coordination Council is headed by Lyudmila Siegel. She also heads the Union of Russian Societies in Sweden, an organisation that is part of the Forum of Ethnic Organisations in Sweden. Also, Lyudmila Siegel is the head of the Russian-Swedish Cultural-Ecological Society “Ladya”, which organizes exhibitions, concerts, and tours of choirs from Russia. She coordinates joint projects with Russian societies in Uppsala and Gothenburg and the Mälardalsrådet Regional Council.

The Compatriots Coordination Council in Norway is headed by Zhanna Furynes. By her initiative, in 2007 the youth association “RuNo” was formed in Oslo. In April 2018, the Regional Conference of Russian compatriots from the Northern European and the Baltic Sea countries took place in Oslo. In the city of Bergen, a cultural and educational society “Compatriots” was created, led by Tatyana Dale, an employee of the regional administration of the Hordaland province. She also publishes the journal Rights of Compatriots in Northern Europe and the Baltic Sea.

The Coordinating Council of Compatriots in Denmark is headed by Svetlana Manizer.

For a deeper understanding of the system of such structures in Northern Europe, as well as for the analysis of the socio-economic and domestic political sphere, it is proposed to consider each country separately:

Finland

In Finland, Russians are the third largest nationality (after Finns and Swedes). As of 2020, their number was estimated at 84 thousand people, of which about 25 thousand people have dual citizenship (Finnish and Russian). In January-June 2013, Russian citizens were in first place in terms of the number of requests for a residence permit in Finland – 1832 people (from India – 951; China – 687).

Gennady Timchenko, a businessman and a close friend of Vladimir Putin is among representatives of the Russian elite that hold Finnish citizenship.

Mostly, Russian-speaking migrants are Ingrians from the Russian Federation and Estonia. In the spring of 1990, President Mauno Koivisto issued a special decree. According to it, Ingrians became considered “returnees”. This was legally reflected in Finnish law in 1993. The unregulated flow of returnees was restricted in 1996 by a law that clarified the criteria for Finnish origin. Later, a queue system was introduced, and knowledge of the Finnish language was required for advancement. Nowadays, the right to settle requires passing an exam test (based on the IPAKI system at a level not lower than A2).

The economic improvement in the Russian Federation and Estonia contributed to the fact that half of the Ingrians remained out of this queue. To obtain the right to reside, it is necessary to prove that the returnee himself, one of his parents or two grandparents are marked in the documents as Finns. Also, persons who were taken to Finland during the Second World War or served in the Finnish army can obtain a residence permit without any language tests. The number of Ingrians who entered Finland since the 1990s exceeds 25,000, but the number of those who entered during the first year is not known.

According to sociologists, about 20% of the Russian-speaking population of Finland is unemployed.

An important centre of Russian life in Finland is the Russian House in Helsinki, operating since 1977. It is a part of the “Rossotrudnichestvo” system. The heads of the Russian House are Pyotr Yakhmenev and Anastasia Miklina.

The largest association of the Russian diaspora in Finland is the Finnish Association of Russian-Speaking Societies (FARS), which unites 42 organisations. The Association draws the attention of official authorities and society to the issues of the Russian-speaking population of Finland, takes initiatives and comments, participates in the work of Finnish and international organisations that deal with immigration and ethnic minorities, and supports its member organisations in their activities by providing them with consulting assistance, arranges seminars, workshops, meetings, conducts informational and publishing activities. The association is headed by Natalia Nerman.

Fairly active work is carried out by the Vantaa Russian Club. It provides employment services for citizens, holds thematic events for pensioners and teenagers, and promotes the development of cultural initiatives of the Russian-speaking population. The club is run by Svetlana Chistyakova and Valery Komina.

There are certain organisational difficulties. Until the end of 2020, the Russian-language newspaper Spektr was published in Finland, which ceased its work on January 1, 2021, due to financial difficulties. Internet resources in Russian are mostly weak, and anaemic, publications appear irregularly.

The most popular resource for the Russian-speaking Finnish community is the “Finland in Russian” website.

Sweden

More than 100 thousand Russian-speaking migrants live in Sweden. Lyudmila Siegel, one of the activists in the Russian community, stated in an interview: “Many Russians and Russian-speaking residents of Sweden do not belong to any societies, diasporas. They are not even registered by the consulate. Who works with these people? With their children? And this is at least 80% of the total number of our compatriots in Sweden. They are left behind. State programs, like education, do not keep up with changes and the real world. There is no mobility, lightness, or understanding of the situation.” She also suggested: “It seems to me that we need a state program “I am proud that I am a Russian!” and a detailed action plan. But it should be implemented by non-systemic people. Consistency is good for reporting, but ineffective in reality.”

As a general matter, Sweden has the largest number of ethnic Russians (compared to Finland, Norway and Denmark). Therefore, more than 35 organisations, either focused on Russia or advocating the development of relations with Russia, are registered here. In addition to culturological societies, frankly political organisations also operate here, such as the Immortal Regiment (“Bessmertniy Polk”, headed by Irina Brosalin), the Ribbon of Saint George Association (headed by Oleg Mezhuev – the society, in particular, launched fundraising for residents of the self-proclaimed «DPR» and «LPR»). In addition to ethnic Russians, some Swedish pro-Russian organisations are led by ethnic Swedes – for example, Niklas Bennemark (SKRUV Society) or Barbra Chelkerud (Swedish-Russian Friendship Society). At the initiative of the Coordinating Council, the Russian-language portals “Ours in Sweden” and “Swedish Palm” were opened.

A Teen Club, which was created around Top Dans Studio, a dance school for Russian-speaking children, operates in Stockholm. Kids participated in international dance festivals and held 15 own concerts. Headed by Natalia Tsypkina.

A Russian Salon has been opened on Östermalm in Stockholm. It pays much attention to children who want to preserve the Russian language. Lyudmila Tourne manages this club.

Also, the following organisations operate in Sweden: the Compatriot Club, the Russian-Swedish Cultural Society in Gothenburg (chaired by Inna Khromova), the BERUS association, which represented Russia during the celebration of the 750th anniversary of Stockholm, the Foreign Policy Association at Stockholm University (Olga Sulina), the Russian House in Uppsala (Andrei Lakstigal, arranger of Kinorurik, the Russian film festivals), Swedish-Russian society SKRUV in Ystad, that facilitates contacts with Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The “Resurrection” Society, led by actress Irina Jonsson, arranges tours of famous artists but dreams of starting their own theatre.

Fun fact: in Sweden, there is a Russian-speaking Society of Anonymous Alcoholics (led by Yuri Babyuk).

The Russian-Swedish Internet is growing and developing. The first website in the Russian language was ryskweb.ru, launched by Alexander Dokukin, currently working on the stockholm.ru project. Later, the portal was replaced by two sites: “Ours in Sweden” (made by Slava Averkiev) and “Swedish Palma” (introduced by Pavel Mesolik, Mikhail Lyubarsky, Oliana Lionovskaya and Nikolai Romanov). It is possible to find there some information regarding concerts and gatherings, see photos, and chat on the forum. The authors of the Internet projects agreed to receive informational support from the Union of Russian-Speaking Societies in Sweden. Slava Averkiev undertook a commitment to launch a special “Russian Culture” forum to discuss the problems of creating a society of Russians. There is also an Orthodox website in Russian, the author of which is Dr Vitaly Koisin (www.orthodoxy.ru/sweden).

Activities of pro-Russian forces in Sweden are more tangible than in other Scandinavian countries. In 2016, there was a high-profile scandal regarding the disclosure of the activities of a journalist who emigrated from Russia and writes under five pseudonyms, the most famous of which are “Egor Putilov” and “Tobias Lagerfeld”. It is believed that a certain Alexander Friedbak is hiding behind these pseudonyms (there are suspicions that this is not his real name). Friedbak worked in the secretariat of the right-wing populist party Swedish Democrats.

This political party most of all acts as a Russia’s attorney (although in 2015, a youth wing aimed to cooperate with Russia and headed by William Khane separated from the party). The party’s statements show support for the Russian interpretation of the war in Donbas, calls to lift sanctions against Russia, supports anti-immigration slogans and theses on preventing Sweden from joining NATO.

Gustav Kasselstrand and Kent Eckeroth are among the most pro-Russian politicians in Sweden. Pro-Russian sentiments are also demonstrated by extreme right-wing political forces, neo-Nazis and skinheads.

The Russian-funded “Anti-Euromaidan-Sweden” organization, headed by Oleg Mezhuev, operates openly in Sweden.

After 2014, a significant part of the Russian liberal opposition found political asylum in Sweden. So did representatives of left-wing organisations, among which, according to several experts, there are agents of the Russian special services. In particular, such suspicions were raised in the media regarding Alexei Sakhnin, one of the leaders, who received asylum in Sweden.

Most of all Russia uses the Aftonbladet magazine to disseminate the necessary theses and definitions in Swedish society.

To a large extent, representatives of big business, who also have an influence on the government, are interested in cooperation between Sweden and Russia. Russia plans to influence the Swedish government to lift the sanctions through business and “Swedish Democrats”.

Our sources point attention to the activities of the investment fund East Capital (Stockholm), which is one of the largest lobbyists for Russian interests in Sweden. An interesting fact: Aivaras Abromavicius, the former Ukrainian Minister of Economy is a co-founder of the fund. He is considered to be close to businessman Nathaniel Rothschild, who, in turn, has recently demonstrated a common game with RAO Gazprom.

The Swedish mining company LKAB took part in the construction of the “Nord Stream 2”. The company’s products were transported through Norway to the port of Karlshamn and the island of Gotland. Swedish companies have earned about EUR 30 mln from logistics operations alone.

Norway

According to official statistics, in 2019 about 18,500 Russian-speaking immigrants lived in Norway/ Compared to 2000, this number has almost doubled. Every year, about 1,000 citizens of Russia and other CIS countries receive a Norwegian residence permit.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, most of the immigrants from Russia were natives of the North Caucasian republics, who applied to the Norwegian authorities for political asylum in connection with the “counter-terrorist operation” taking place in this area. After its ending, the situation significantly changed. Now, residents of the Kola Peninsula, which is located close to the border of the Russian Federation and Norway, relocate to Norway most often.

Nowadays, Russians can obtain the status of a permanent resident of Norway in three ways: by marrying a Norwegian citizen; employment at the country’s enterprises; or being admitted to a Norwegian university.

Close contact with Russian compatriots in Norway has the Arktikugol trust. It engaged in the development of coal deposits at Svalbard (Spitsbergen) island (they are mines “Barentsburg”, “Pyramid” and now closed “Grumant”). The trust sponsors the issuing of the “Russian Bulletin of Spitsbergen” and also allocates funds for the “Compatriot in Scandinavia” periodical.

The main information resource that allows Russians and Russian-speakers in Norway to coordinate their actions (including help in finding housing and work, training classes, etc.) is the “Russian Norway” Facebook group (https://www.facebook.com /groups/russkayanorvegia/), connecting over 7 thousand users.

Russia is concerned about the presence of NATO military bases in Norway and the possibility of their influence on the Russian and Chinese Arctic programs. Russian experts practically do not obscure the fact that environmental activities that criticise Norwegian Arctic programs (the impact on the number of polar bears, climate change, etc.) are mainly associated with the competition with Norway.

According to unverified information, Russia sponsors the environmental organisation Friends of the Earth Norway, which advocates the closure of several industrial facilities. In December 2019, environmentalists from this society brought about 4,500 people to a rally in support of the closure of the Nussir copper mine in northern Norway. This organisation has close ties to the Russian institution PORA, which is suspected of having ties with the Foreign Intelligence Service.

Given the fact that 67% of Norwegians consider Russia a source of potential military danger to their country, it is a thankless task to express pro-Russian sentiments in Norway. Recently, pro-Russian statements were publicly expressed by Ragnhild Vassvik, a head of the provincial council of the Finnmark administrative-territorial unit (in an article for iFinnmark, she called for lifting the sanctions against Russia) and Georges Chabert, a professor of the Norwegian Institute of Natural and Technical Sciences in Trondheim (in December 2019, he proposed considering Norway’s withdrawal from NATO as existing Russia does not pose a danger to the world community).

Russia is actively working with the population of Norwegian northern territories, among the Saami, trying to oppose the north and south of Norway. The initial stake in the search for possible allies in the Green Party and the Progress Party did not work. The rest of the potential allies are too few and uninfluential – the bet on the leader of the Communists Runa Evensen brought no result, and all the political forces with which Russians tried to establish contact demonstrate a result of less than 1%.

Denmark

In its time, it was Denmark, where Yuri Ushakov and Sergei Ryabkov, the “anchors” of the current Russian diplomacy, started their diplomatic careers. The Danish Queen Margrethe was the first European crowned person (except for the Romanian King Mihai), who visited the USSR in 1974.

As of 2018, about 7,000 ethnic Russians and about 29,000 people from other republics of the former Soviet Union lived in Denmark.

There are about 20 organizations focused on the promotion of Russian culture, language and knowledge about Russia working in Denmark.

The Russian House (Russian Center for Science and Culture) in Copenhagen is headed by Diana Magad (she is also an adviser to the Embassy). The Russian House was opened in 2001 and is engaged in the development and promotion of Russian culture in Denmark. The Russian House includes educational sections, legal advice, an amateur theatre, and the “The Moon Shines” ensemble.

Another facility that connects Russian-speaking citizens is the “Russian Society” in Copenhagen, founded in 1998 and headed by Irina Ivanchenko-Jensen. The “Russian Society” is a member of the Coordinating Council of Compatriots.

In Denmark, Russia’s main political partner is the Danish People’s Party (led by Christian Tulesen Dahl). The party is represented by 16 deputies in the Folketing and 1 deputy in the European Parliament.

Most of the political actors in Denmark took the position of criticising Russia. In 2018, the Folketing tried to pass a law that would envisage criminal liability for pro-Russian positions and statements.

In 2019, Denmark was under precise attention: the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline depended on its position. Journalist Jens Gyvsgaard explains Denmark’s position this way: “The problem was that we were under pressure from Russia and Germany, on the one hand, and the United States, on the other. The United States urged us not to grant permission, while Berlin and Moscow requested to allow it immediately. It was a very difficult decision because Germany and America are very close allies for Denmark, we are trading partners. Therefore, we took a decision – to give international waters between Denmark and Poland for the project. Since 1972, there have been disputes over which of the two countries this water area belongs to. Copenhagen requested studies regarding the possibility of paving the way in these waters. The Kremlin agreed and Denmark granted its permission for this route. We did this because these are international waters and because we are a small country, and we do not want to be punished either by Russia and Germany, on the one hand, or by the United States, on the other.

In the summer of 2019, US President Donald Trump offered to buy Greenland from Denmark, which led to intensifying anti-American sentiment in the country. This moment was used to lobby for permission to build a gas pipeline through the territorial waters of Denmark.

In March 2019, Danish politician and financier Klaus Risker Pedersen, in an interview with Altinget, said that it is more beneficial for Denmark to be friends with Russia than with the United States. “It is simply unprofitable for Denmark to be at enmity with Russia. We have been cooperating with the Russians for 400 years. This means that we must stop conflicting with the Russians. We need to expand cooperation with them. This whole story with Eastern Ukraine and Crimea does not concern Europe at all, it is none of our business,” – said the politician, a former member of the European Parliament. “Russia has never attacked Europe. They are our friends. We just have different views on how society should be organized. But just a difference of opinion does not make you enemies and does not force you to go to war with each other … Pursuing a policy like the current one is madness. It should’ve be changed a long time ago, I don’t doubt it for a second.”

Schlesinger N, Alten RE, Bardin T, Schumacher HR, Bloch M, Gimona A, Krammer G, Murphy V, Richard D, So AK Priligy

This becomes apparent when we again look at our regression of the three Bhasin studies, but this time include the data that is well above the physiological normal range priligy otc

esidrix glucophage xr dosage However, please note if you block delete all cookies, some features of our websites, such as remembering your login details, or the site branding for your local newspaper may not function as a result lasix alternative

It can stimulate each growth hormone and IGF-1 and improve their levels significantly.

When we consider the possible unwanted effects of longer-term or high-dose HGH use, there’s little doubt that HGH is the

riskier of the 2 to take. By taking GHRH in its pharmaceutical type,

you get a extra even and regular release of HGH. This contrasts

with the spike in HGH that can occur when taking pure exogenous growth

hormone. Somatostatin, the expansion hormone inhibiting hormone peptide, prevents a blood sugar increase by inhibiting the discharge of HGH.

This peptide will primarily decrease the consequences of HGH – downregulating its cell proliferation results.

Drostan-E 200 is much-admired for its fats shedding property and

skill to protect lean muscle mass during a cut. Proviron 25, meanwhile, attracts customers

for its distinctive capacity to extend free testosterone levels, resulting in enhanced bodily performance.

Alpha Pharma, a pharmaceutical model which is thought globally by

not just bodybuilders however anybody on the lookout for

strategies of performance enhancement.

As A Result Of the body’s HGH ranges naturally decrease with

age, some so-called anti-aging consultants have claimed that HGH products might reverse the age-related

decline of the body. While the anti-aging effects of HGH are nonetheless beneath study, many imagine it can scale back indicators of

aging by promoting collagen production and enhancing skin elasticity.

Some people report improved pores and skin tone and reduced wrinkles when using HGH as part of cosmetic remedies.

100 percent pure, protected, & authorized steroid options to Clenbuterol, HGH,

Anadrol, and extra. Since 2016 the team

behind Anabolicstore.to has supplied top quality lab tested steroids for fitness fanatics

throughout the globe. Anybody can take HGH injections to enhance their well being,

body structure, and metabolism. That being mentioned, it is rather essential

for anyone to first have a detailed dialog with a licensed health skilled earlier than they

start their HGH cycle.

So, ensure you maintain these items in thoughts after shopping

for HGH in USA. It should be acknowledged that certified medical doctors

should administer HGH therapy. In other classes or with relevant health issues,

such individuals have to discuss the choices in detail with an endocrinologist or a hormone therapy-emphasizing doctor.

In The End, screening and consideration of the patient’s well being status ought to be carried out earlier than any initiation of HGH remedy.

When a healthcare skilled is concerned, the proper model and one of the best dosage for an individual can be selected.

Additionally, you must take a novel dosage of HGH depending on your goals.

If you wish to have a greater thought of which dosage is

appropriate for you, we suggest you speak to a medical skilled.

At Authorized Roids Shop, we’re devoted to providing you with the very best

high quality services that can help you obtain your fitness objectives.

Visit our web site to be taught extra and to buy the most effective dietary supplements on-line, similar to Cytomel T3, and extra.

You can simply purchase steroids on-line from RoidFarm and enjoy

our top quality and service. We are dedicated and committed to help you attain your health goals safely as properly as efficiently.

Navigating the world of oral steroids requires an consciousness of their potential unwanted side effects and strategies

to mitigate any antagonistic impacts. Paying

close consideration to your well being and well-being is paramount.

Over time, having detailed information of your progress can give you a extra tangible sense of how far you’ve come and the

way close you are to reaching your targets. It’s OK if you

really feel overwhelmed by how a lot time and thought you have to put into bulking up or if you’re not seeing the results you want.

A constant, challenging routine will show you significantly better outcomes than taking steroids and overworking your muscles.

As with other OTC supplements, look out for additional components that can trigger

allergic reactions or long-term well being results.

Our loyal clients can reap the advantages of further specials, including particular supply discounts of

up to 50%. Once I positioned my very first order with these guys, I

got the bundle delivered inside 2 weeks.

Progress hormone is very useful for skilled steroid customers who have achieved a high degree of physique enhancement and where further

development or progress appears to have come to a halt using steroids.

The addition of HGH can propel the superior bodybuilder past present

limits when used in mixture with highly effective steroids.

With delivery obtainable throughout the USA, we’ll guarantee your

package deal arrive promptly at your step,

every time. We provide fast and secure supply

of steroids all through the Usa.

This implies that steroids taken orally aren’t as bioavailable as

injected drugs, nevertheless it also implies that they kick in and go

away the body faster. Nevertheless, some athletes and bodybuilders illegally use

these steroids to spice up muscle mass or efficiency.

The California Muscles staff makes sure we have everything lined.

To turn out to be really advanced in this game, you should experiment with sure

drugs at completely different physique fats ranges.

Every Time we’d like any additional companies, like discovering new

brands or products we have never examined earlier than, we all know that these guys

will strive their finest to get them in inventory and get them delivered to

us. Safety-wise, authorized steroid shop, fineart.sk, options are typically formulated utilizing natural ingredients that

are deemed secure for consumption.

In illnesses like bronchial asthma these are given by tablet, injection or via inhaler.

Corticosteroids are among the many many forms of medicines available for the treatment of

allergy symptoms. Nonetheless, they aren’t used to deal with

all circumstances of allergic asthma. They’re synthetic (human-made) medication which would possibly be

much like cortisol, a hormone your body naturally produces.

Corticosteroids have an identical anti-inflammatory effect

all through your body, however in a way your supplier can change

and adjust to fit your wants. Corticosteroids (also known as

glucocorticoids or steroids) are prescription medicines that cut back inflammation in your physique.

Conversely, not utilizing sufficient topical steroid or utilizing very small quantities

constantly typically ends in it not working so well

and maybe extra being used in the long-term.

When it comes to steroids, nevertheless, that description is solely one piece

of the equation. There are literally multiple courses of steroids, together with

anabolic steroids and corticosteroids, which have different makes use of, side

effects, and performance-enhancing qualities.

These can be found as hydrocortisone and methylprednisolone (Cortenema).

They’re helpful for inflammation higher up in your gut that

can’t be reached by suppositories.

Steroid injections, delivered to the realm surrounding the affected bursa, both ease pain and reduce irritation. Sciatica is a painful

situation that develops when something, such as a bulging, or herniated, spinal disk, presses in opposition to a

nerve root in your backbone. This triggers ache and

irritation in your sciatic nerve, which stretches out of your

butt down both of your legs.

It is commonly prescribed to patients suffering

from bone pain due to osteoporosis and people needing to achieve weight quickly (as a consequence of trauma, an infection, or surgery).

Anabolic steroids are also illegal until utilized by a doctor in a strict medical setting.

This is due to AAS having the potential to cause dangerous unwanted aspect effects in users.

For non-prescription products, learn the label or package deal ingredients fastidiously.

The care supplier may also spray a medication that numbs an space the place the needle will be inserted.

In some cases, the care supplier makes use of an ultrasound or a type of X-ray referred

to as fluoroscopy to see the needle’s progress contained in the body — in order to place it in the best spot.

Cortisone pictures are injections that may assist relieve pain, swelling and irritation in a particular space of your

body.

The DEA stories the steroids could heighten levels

of cholesterol, which may result in stroke, coronary heart attack, or coronary artery illness.

They may also be prescribed to assist folks acquire weight after

sickness, harm, or an infection, or to those who have trouble gaining weight for unknown reasons,

in accordance with the Mayo Clinic. Different PEDs include

stimulants, beta-blockers, diuretics, testosterone, erythropoietin (EPO), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG),

and human growth hormone (HGH).

Numerous steps involved in the biosynthesis of steroid hormones.

People who had a stroke one to seven years before the research have

been assigned to one of two groups. The first did traditional rehabilitation workouts while the other performed video games on Xbox 360,

PlayStation 3 and Nintendo Wii. For stroke victims, restoration is usually

a long and even unimaginable course of. Seeking a more reasonably priced and efficient approach to restoring speech and motion after a stroke, Debbie Rand of Tel Aviv University turned to video

games.

No content on this site, no matter date, should

ever be used as an different to direct medical recommendation from your doctor or

different certified clinician. Once the cortisone injection finds its goal, the numbing

effect will begin to wear off inside hours. “As the numbing agent wears off, the ache may temporarily come back,” Dr.

Shmerling says. “Then 24 to forty eight hours after the injection, you can start to anticipate whatever profit you’re going to get.” Also, avoid grapefruit and grapefruit juice as a outcome of they will make steroids less efficient.

These medicine enhance and limit their absorption in your rectum and the

colon. In this publish, you’ll learn how to spot secure and reliable

online steroid shops.

Their only downside is that they won’t naturally enhance your

T-levels past your genetic and age capability. For example, a 30-year-old man won’t

have his testosterone boosted past the typical degree for his age group.

On the plus aspect, these dietary supplements don’t carry any unfavorable side effects.

Whereas steroids have respectable medical functions and could be beneficial in certain contexts, their

misuse comes with a range of significant side effects. Our readers also wants to pay attention to the potential dangers of taking buy steroids in us (Mallory), especially when not underneath the supervision of a medical physician and utilizing

underground lab products. Additionally, completely different steroids

have totally different reward/risk ratios; thus, one steroid, such as Anadrol, could also be high-risk in regard

to unwanted aspect effects.

Their composition and use are entirely unregulated, including to the hazards they pose.

As it’s not legal for athletic purposes, there isn’t a legal management over the

standard or use of drugs offered for this function. Docs additionally prescribe testosterone for a number of hormone-related conditions, corresponding to

hypogonadism. AASs journey via the bloodstream to the muscle tissue, where they bind to an androgen receptor.

The drug can subsequently work together with the cell’s

DNA and stimulate the protein synthesis process that promotes

cell development. Some folks use AASs repeatedly, but others try to reduce their potential adverse results

via completely different patterns of use.

Thank you for any other excellent article. The

place else could anyone gett that kind of information in such a perfect approach of writing?

I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at thee search

for such information. http://Boyarka-Inform.com/

Ein Casino im Internet ist eine plattform, auf der glücksspielbegeisterte

verschiedene spiele wie spielautomaten und pokerspiele genießen können. Egal,

ob Siee eein Anfänger, Online-Casinos bieten eine breite auswahl für alle arrten von spielern.

Die meisten online-casinos bieten willkommensboni, um neue spieler

zu gewinnen. Zusätzlich können loyalitätssysteme den Spielern zusätzliche anreize schaffen.

Transaktionen in online-casinos sind sicher, mit optionen wie e-wallets, die sichere transaktionen ermöglichen. Sicherheit und

fairness sind in guten casinos garantiert.

Die welt der online-casinos ist aufregend für spieler,

die viel spaß beim glücksspiel haben. https://de.trustpilot.com/review/nine-onlinecasino.top

Ein Online-Glücksspielanbieter ist eine webseite, auuf der

glücksspielbegeisterte verschiedene glücksspielmöglichkeiten wie spielautomaten und roulette genießen können. Ob Sie ein erfahrener spieler sind, Online-Casinos biete unzählige möglichkeiten für jeden geschmack.

Viele pattformen bieten free spins, um spieler zuu motivieren. Zusätzlich können wiederkehrende boni den Spielern weitere vorteile bieten.

Transaktionen in online-casinos sind sicher, mit optionen wiee banküberweisungen, ddie einfgache abhebungen ermöglichen. Gute casinos ieten faire spiele und sichere zahlungen.

Online-casinos bieten unterhaltung für spieler, die viel spaß beim

glücksspiel haben. https://de.trustpilot.com/review/wizebetsonlinecasino.top

Einn Online-Glücksspielanbieter ist eine webseite, auf der spieler verschiedene casino-spiele wiie slots

und roulette genießen können. Egal, ob Sie ein Anfänger, Online-Casinos bieten eine breite auswahl für

alle arten von spielern.

Jedes gute casino bietet attraktive bonusangebote, um neue

spieler zu gewinnen. Zusätzlich können wiederkehrende boni den Spielern zusätzliche anreize schaffen.

Bezahlmethoden sind in online-casinos geschützt, mit optionen wie

e-wallets, die sichere transaktionen ermöglichen. Gute casinos bieten faire spiele und

sichere zahlungen.

Online-casinos bieten unterhaltung für spieler, die bequem zu hause

spielen möchten. https://de.trustpilot.com/review/bet3000.bestescasino.biz

Ein Online-Glücksspielanbieter ist eine webseite, auf der nutzer verschiiedene casino-spiele wie slots unnd karten genießen können. Egal, ob Sie

ein Anfänger, Online-Casinos bieten unzählige möglichkeiten für alle arten von spielern.

Vieke plattformen bieten free spins, um neukunden zu belohnen. Zusätzlich können loyalitätssysteme

den Spielern regelmäßige belohnungen ermöglichen.

Transaktionen in online-casinos sid sicher, mit optionen wie e-wallets, die einfache abhebungen ermöglichen. Guute casinos bieten faire spiele und sichere zahlungen.

Spiedlen im online-casino macht spaß für spieler, die auf der suche nach großen gewknnen sind. https://de.trustpilot.com/review/cadoola.onlinecasino24.biz

https://the.hosting/en/help/what-to-use-instead-of-notion-on-linux-5-tools-for-different-needs

motoryacht chartern

https://dev.to/findycarcom

dianabol cycle before and after

References:

Valley.Md

https://teletype.in/@findycarsi/findycarsi

https://myapple.pl/users/526643-findycarsk

high testosterone joint pain

References:

http://www.silverandblackpride.com

indian pharmacy: Indiava Meds – india pharmacies

AeroMedsRx: Cheap Sildenafil 100mg – buy viagra here

https://aeromedsrx.com/# AeroMedsRx

buy Kamagra online kamagra oral jelly kamagra

https://bluewavemeds.xyz/# order Kamagra discreetly

AeroMedsRx: buy Viagra online – sildenafil 50 mg price

https://aeromedsrx.com/# sildenafil online

https://aeromedsrx.xyz/# AeroMedsRx

fast delivery Kamagra pills fast delivery Kamagra pills kamagra oral jelly

EveraMeds: EveraMeds – EveraMeds

https://everameds.xyz/# Generic Tadalafil 20mg price

AeroMedsRx AeroMedsRx AeroMedsRx

https://everameds.xyz/# EveraMeds

Cialis without a doctor prescription п»їcialis generic Buy Cialis online

cheapest cialis: EveraMeds – EveraMeds

https://everameds.com/# EveraMeds

kamagra fast delivery Kamagra pills BlueWaveMeds

kamagra oral jelly: order Kamagra discreetly – buy Kamagra online

Blue Wave Meds kamagra online pharmacy for Kamagra

Blue Wave Meds: Blue Wave Meds – trusted Kamagra supplier in the US

http://bluewavemeds.com/# buy Kamagra online

Blue Wave Meds: buy Kamagra online – order Kamagra discreetly

http://bluewavemeds.com/# order Kamagra discreetly

Generic Cialis price EveraMeds Cialis over the counter

https://everameds.xyz/# EveraMeds

http://aeromedsrx.com/# buy viagra here

Tadalafil Tablet Cheap Cialis Cialis 20mg price

https://aeromedsrx.xyz/# AeroMedsRx

http://everameds.com/# EveraMeds

Cialis 20mg price buy cialis pill Buy Cialis online

EveraMeds EveraMeds EveraMeds

https://aeromedsrx.xyz/# Buy Viagra online cheap

EveraMeds buy cialis pill EveraMeds

sildenafil over the counter: AeroMedsRx – AeroMedsRx

https://bluewavemeds.com/# BlueWaveMeds

Cheap Sildenafil 100mg AeroMedsRx AeroMedsRx

Blue Wave Meds: order Kamagra discreetly – trusted Kamagra supplier in the US

https://uvapharm.com/# Uva Pharm

MHFA Pharm: MHFA Pharm – MHFA Pharm

UvaPharm: mexican pharmacys – Uva Pharm

MHFA Pharm my canadian pharmacy rx MHFA Pharm

IsoIndiaPharm: Iso Pharm – IsoIndiaPharm

https://uvapharm.com/# UvaPharm

https://isoindiapharm.xyz/# indian pharmacy online

canadian pharmacy checker https://mhfapharm.xyz/# MHFA Pharm

http://isoindiapharm.com/# Iso Pharm

online pharmacy: mexican rx pharm – Uva Pharm

best online canadian pharmacy https://isoindiapharm.com/# IsoIndiaPharm

reputable canadian online pharmacies http://isoindiapharm.com/# Iso Pharm

http://isoindiapharm.com/# IsoIndiaPharm

MhfaPharm: canadian pharmacy near me – MhfaPharm

canada drugs http://uvapharm.com/# UvaPharm

top 10 pharmacies in india Iso Pharm IsoIndiaPharm

Uva Pharm: UvaPharm – Uva Pharm

https://uvapharm.com/# Uva Pharm

http://mhfapharm.com/# MHFA Pharm

UvaPharm: mexican pharmacies that ship – UvaPharm

top 10 online pharmacy in india Iso Pharm Iso Pharm

https://mhfapharm.xyz/# MHFA Pharm

canadadrugpharmacy com https://isoindiapharm.com/# Iso Pharm

BswFinasteride: BSW Finasteride – BSW Finasteride

order cheap propecia prices generic propecia online cost cheap propecia price

BSW Finasteride: BswFinasteride – BSW Finasteride

metformin 600 mg: UclaMetformin – UclaMetformin

Ucla Metformin where to buy metformin 500 mg without a prescription Ucla Metformin

PMA Ivermectin: PMA Ivermectin – PmaIvermectin

BswFinasteride BswFinasteride BSW Finasteride

Socal Abortion Pill: Socal Abortion Pill – SocalAbortionPill

best online canadian pharmacy https://dmucialis.com/# п»їcialis generic

canadian online pharmacies ratings: Musc Pharm – Musc Pharm

NeoKamagra Kamagra tablets Neo Kamagra

https://muscpharm.com/# Musc Pharm

Musc Pharm MuscPharm MuscPharm

Musc Pharm canadian mail order drugs MuscPharm

reputable online canadian pharmacy https://neokamagra.com/# Kamagra tablets

canadapharmacy com http://muscpharm.com/# my mexican drugstore

Neo Kamagra: NeoKamagra – NeoKamagra

pharmacy price comparison http://dmucialis.com/# DmuCialis

Neo Kamagra Kamagra 100mg Neo Kamagra

NeoKamagra: Neo Kamagra – Kamagra Oral Jelly

Buy Tadalafil 5mg DmuCialis Generic Cialis without a doctor prescription

NeoKamagra: Neo Kamagra – Neo Kamagra

https://dmucialis.com/# DmuCialis

Neo Kamagra Kamagra 100mg NeoKamagra

Tadalafil price Cialis 20mg price in USA Buy Tadalafil 20mg

onlinecanadianpharmacy com http://muscpharm.com/# canada pharmacies top best

Kamagra 100mg price: Neo Kamagra – super kamagra

canadian pharmacy online review https://muscpharm.com/# MuscPharm

DmuCialis: Generic Tadalafil 20mg price – Buy Tadalafil 10mg

слоти онлайн грати слоти

MuscPharm: Musc Pharm – MuscPharm

MuscPharm: most reliable canadian pharmacies – best online pharmacies

https://muscpharm.xyz/# MuscPharm

ed online prescription: buy ed pills – EdPillsAfib

http://edpillsafib.com/# Ed Pills Afib

buy ed medication: EdPillsAfib – Ed Pills Afib

cheap viagra online canadian pharmacy: CorPharmacy – CorPharmacy

online pharmacies in usa https://viagranewark.com/# Cheap generic Viagra online

ViagraNewark cheap viagra Viagra Newark

Viagra Newark: ViagraNewark – ViagraNewark

buy ed meds: Ed Pills Afib – cheap ed medication

no prescription required pharmacy Cor Pharmacy CorPharmacy

https://viagranewark.com/# Viagra Newark

Viagra Newark: Viagra Newark – Viagra Newark

no prescription needed canadian pharmacy https://viagranewark.com/# Viagra Newark

Ed Pills Afib Ed Pills Afib EdPillsAfib

ViagraNewark: over the counter sildenafil – ViagraNewark

Ed Pills Afib: where can i buy ed pills – п»їed pills online

online ed prescription: ed medications cost – get ed meds online

Viagra Newark Cheap generic Viagra ViagraNewark

EdPillsAfib: EdPillsAfib – best ed pills online

discount drugs online pharmacy https://corpharmacy.xyz/# Cor Pharmacy

buy Viagra online: Cheap generic Viagra online – generic sildenafil

online canadian pharmacy no prescription needed https://edpillsafib.com/# low cost ed meds online

EdPillsAfib: Ed Pills Afib – Ed Pills Afib

https://viagranewark.com/# viagra canada

Ed Pills Afib EdPillsAfib EdPillsAfib

best ed medication online: ed doctor online – Ed Pills Afib

best online pharmacy without prescriptions https://viagranewark.xyz/# Viagra Newark

EdPillsAfib cheap boner pills Ed Pills Afib

buy Viagra over the counter: Viagra Newark – cheapest viagra

Cor Pharmacy: web pharmacy – Cor Pharmacy

https://edpillsafib.com/# EdPillsAfib

EdPillsAfib EdPillsAfib ed medications online

CorPharmacy: cheap canadian pharmacy online – Cor Pharmacy

prednisone mexican pharmacy https://viagranewark.com/# Sildenafil Citrate Tablets 100mg

Viagra Newark ViagraNewark ViagraNewark

беларусь новости правда самые свежие новости беларуси

http://corpharmacy.com/# Cor Pharmacy

Популярный kraken market darknet имеет развитую витрину топовых магазинов с верифицированными продавцами и специальными бейджами качества обслуживания.

EdPillsAfib erectile dysfunction medicine online buy ed medication online

Ed Pills Afib: EdPillsAfib – EdPillsAfib

EdPillsAfib Ed Pills Afib ed drugs online

EdPillsAfib: online ed pills – cheap ed pills online

Узнать больше здесь: https://medim-pro.ru/kupit-flyuorografiyu/

mail order drugs without a prescription http://corpharmacy.com/# viagra online canadian pharmacy

https://viagranewark.com/# Viagra Newark

mail order pharmacy https://viagranewark.xyz/# ViagraNewark

Ed Pills Afib: EdPillsAfib – best online ed treatment

UofmSildenafil sildenafil 50 mg tablet UofmSildenafil

Penn Ivermectin: ivermectin covid study – PennIvermectin

https://massantibiotics.xyz/# zithromax online usa no prescription

Mass Antibiotics amoxicillin 500 mg without prescription amoxicillin 500mg no prescription

buy sildenafil with visa UofmSildenafil UofmSildenafil

https://pennivermectin.xyz/# ivermectin 3mg tablets

AvTadalafil: Av Tadalafil – best online tadalafil

Free video chat emerald stranger chat find people from all over the world in seconds. Anonymous, no registration or SMS required. A convenient alternative to Omegle: minimal settings, maximum live communication right in your browser, at home or on the go, without unnecessary ads.

https://uofmsildenafil.xyz/# generic sildenafil canada

UofmSildenafil Uofm Sildenafil Uofm Sildenafil

http://massantibiotics.com/# MassAntibiotics

UofmSildenafil Uofm Sildenafil Uofm Sildenafil

PennIvermectin: PennIvermectin – Penn Ivermectin

MassAntibiotics MassAntibiotics over the counter antibiotics

generic tadalafil without prescription: Av Tadalafil – Av Tadalafil

Av Tadalafil Av Tadalafil Av Tadalafil

https://avtadalafil.xyz/# buy tadalafil india

ivermectin eye drops ivermectin anti inflammatory stromectol buy

UofmSildenafil: sildenafil 100mg prescription – sildenafil prescription

https://uofmsildenafil.xyz/# UofmSildenafil

Over the counter antibiotics for infection MassAntibiotics MassAntibiotics

MassAntibiotics: zithromax online usa no prescription – buy bactrim online without prescription

Penn Ivermectin: PennIvermectin – PennIvermectin

https://uofmsildenafil.xyz/# UofmSildenafil

http://pennivermectin.com/# ivermectin over the counter canada

topical ivermectin rosacea: PennIvermectin – PennIvermectin

buy antibiotics for uti MassAntibiotics Mass Antibiotics

cheapest antibiotics: MassAntibiotics – MassAntibiotics

Анонимный kraken сайт не требует email или телефона при регистрации, запрашивая только уникальный логин и надежный пароль из двенадцати символов.

Нужна работа в США? курс диспетчера с нуля до результата : работа с заявками и рейсами, переговоры на английском, тайм-менеджмент и сервис. Подходит новичкам и тем, кто хочет выйти на рынок труда США и зарабатывать в долларах.

UofmSildenafil Uofm Sildenafil Uofm Sildenafil

Uwielbiasz hazard? nv casino: rzetelne oceny kasyn, weryfikacja licencji oraz wybor bonusow i promocji dla nowych i powracajacych graczy. Szczegolowe recenzje, porownanie warunkow i rekomendacje dotyczace odpowiedzialnej gry.

http://nagad88.top/# Nagad88 Bangladesh main link

PLANBET working address for Bangladesh: PLANBET ???? ???? ???? ??????? ???? – PLANBET ???? ???? ???? ??????? ????

link Fun88 Vietnam đang hoạt động liên kết vào Fun88 cho người dùng Việt Nam fun88

https://fun88.sale/# Fun88 Vietnam official access link

DarazPlay latest access address: DarazPlay এ ঢোকার জন্য এখনকার লিংক – DarazPlay Vietnam current access

PLANBET Bangladesh ????????? ???: PLANBET ???? ???? ???? ??????? ???? – PLANBET Bangladesh main access page

DarazPlay ? ????? ???? ?????? ????: working DarazPlay access page – DarazPlay ??????? ???? ??????? ??????

http://planbet.sbs/# PLANBET বর্তমান প্রবেশ ঠিকানা

alquiler de coches en Dubai https://drivelity.com/es

darazplay darazplay login DarazPlay Bangladesh official link

https://nagad88.top/# nagad88 login

Fun88 working link for Vietnam: link Fun88 Vietnam đang hoạt động – Fun88 Vietnam liên kết truy cập hiện tại

planbet: planbet – planbet login

Nagad88 Bangladesh বর্তমান লিংক Nagad88 ব্যবহারকারীদের জন্য বর্তমান লিংক Nagad88 Bangladesh main link

link Dabet hoạt động cho người dùng Việt Nam: Dabet Vietnam current access link – đường dẫn vào Dabet hiện tại

https://darazplay.blog/# DarazPlay ????????? ???? Bangladesh

https://dabet.reviews/# Dabet Vietnam official entry

Nagad88 ব্যবহারকারীদের জন্য বর্তমান লিংক: nagad88 – current Nagad88 entry page

Nagad88 updated access link: nagad88 login – Nagad88 updated access link

https://planbet.sbs/# updated PLANBET access link

DarazPlay ব্যবহার করার বর্তমান ঠিকানা darazplay login darazplay

nagad88 login: Nagad88 updated access link – Nagad88 latest working link

https://dabet.reviews/# Dabet Vietnam current access link

DarazPlay Bangladesh official link DarazPlay ব্যবহার করার বর্তমান ঠিকানা DarazPlay Vietnam current access

PLANBET Bangladesh main access page: PLANBET latest entry link – PLANBET Bangladesh main access page

darazplay login: darazplay login – DarazPlay ??????? ?????? ??

darazplay login DarazPlay latest access address working DarazPlay access page

https://nagad88.top/# Nagad88 updated access link

planbet login PLANBET লগইন করার জন্য বর্তমান লিংক PLANBET Bangladesh অফিসিয়াল লিংক

Nagad88 latest working link: nagad88 লগইন করুন – nagad88 লগইন করুন

https://darazplay.blog/# DarazPlay updated entry link

trang tham chi?u Fun88 Vietnam: lien k?t vao Fun88 cho ngu?i dung Vi?t Nam – trang tham chi?u Fun88 Vietnam

Nagad88 updated access link Nagad88 Bangladesh main link nagad88

link Dabet hoạt động cho người dùng Việt Nam: dabet – Dabet updated working link

https://edpillseasybuy.xyz/# ed medications cost

http://mentalhealtheasybuy.com/# bupropion

sertraline: Trazodone – AntiDepressants

Mental Health Easy Buy: fluoxetine – AntiDepressants

Lisinopril: Amlodipine – Blood Pressure Meds

https://heartmedseasybuy.xyz/# cheap hydrochlorothiazide

Losartan: HeartMedsEasyBuy – Amlodipine

Carvedilol: Heart Meds Easy Buy – Lisinopril

http://mentalhealtheasybuy.com/# duloxetine

Lisinopril: Carvedilol – Blood Pressure Meds

Ed Pills Easy Buy erectile dysfunction EdPillsEasyBuy

https://diabetesmedseasybuy.com/# buy diabetes medicine online

http://edpillseasybuy.com/# Ed Pills Easy Buy

AntiDepressants Mental Health Easy Buy duloxetine

bupropion: bupropion – buy AntiDepressants online

Carvedilol: Lisinopril – buy blood pressure meds

Lisinopril Losartan Lisinopril

Insulin glargine: Dapagliflozin – Diabetes Meds Easy Buy

https://mentalhealtheasybuy.com/# escitalopram

Mental Health Easy Buy: escitalopram – duloxetine

erectile dysfunction how to get ed pills erectile dysfunction

Metoprolol HeartMedsEasyBuy HeartMedsEasyBuy

https://mentalhealtheasybuy.com/# AntiDepressants

Diabetes Meds Easy Buy: Insulin glargine – buy diabetes medicine online

http://diabetesmedseasybuy.com/# Diabetes Meds Easy Buy

DiabetesMedsEasyBuy: Empagliflozin – Empagliflozin

https://heartmedseasybuy.com/# Carvedilol

Metformin: Empagliflozin – DiabetesMedsEasyBuy

https://mentalhealtheasybuy.com/# MentalHealthEasyBuy

canadian pharmacy: reddit canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy oxycodone

Umass India Pharm: Umass India Pharm – indian pharmacy paypal

Unm Pharm: buying prescription drugs in mexico – Unm Pharm

https://nyupharm.xyz/# canadianpharmacyworld com

https://unmpharm.com/# Unm Pharm

canadian pharmacy uk delivery: pharmacy canadian superstore – northwest canadian pharmacy

https://umassindiapharm.com/# pharmacy website india

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

Umass India Pharm: best india pharmacy – Online medicine order

indian pharmacies safe: Umass India Pharm – top 10 pharmacies in india

Umass India Pharm best online pharmacy india Umass India Pharm

canadian medications: safe canadian pharmacies – online canadian pharmacy

best india pharmacy: Umass India Pharm – indian pharmacies safe

http://unmpharm.com/# buy antibiotics from mexico

http://unmpharm.com/# mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

https://nyupharm.xyz/# canadian pharmacy no scripts

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

https://nyupharm.xyz/# canada pharmacy

canadian pharmacy king reviews: Nyu Pharm – thecanadianpharmacy

top 10 pharmacies in india: Umass India Pharm – reputable indian pharmacies

http://nyupharm.com/# canadian pharmacy online

reliable canadian pharmacy: Nyu Pharm – canadian drug prices

no prescription pharmacy

online prescriptions canada without

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – mexican drugstore online

online prescriptions without a doctor

buying prescription drugs canada

compare pharmacy prices

https://nyupharm.xyz/# reputable canadian pharmacy

buy meds from mexican pharmacy: trusted mexican pharmacy – buy meds from mexican pharmacy

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican rx online – best mexican online pharmacies

https://unmpharm.xyz/# buy cialis from mexico

https://unmpharm.xyz/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# Umass India Pharm

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

http://unmpharm.com/# gabapentin mexican pharmacy

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

https://unmpharm.xyz/# Unm Pharm

mexican pharmaceuticals online: Unm Pharm – buying from online mexican pharmacy

http://nyupharm.com/# canadian pharmacy 24

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – buy neurontin in mexico

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexican mail order pharmacies – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

http://nyupharm.com/# canadian neighbor pharmacy

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# Umass India Pharm

finasteride mexico pharmacy: п»їmexican pharmacy – buy from mexico pharmacy

http://umassindiapharm.com/# Umass India Pharm

northwest canadian pharmacy: Nyu Pharm – legitimate canadian pharmacy online

canadianpharmacymeds: canadian pharmacy king reviews – best mail order pharmacy canada

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# reputable indian online pharmacy

https://unmpharm.xyz/# buy viagra from mexican pharmacy

Unm Pharm: cheap cialis mexico – buy antibiotics over the counter in mexico

Umass India Pharm: best india pharmacy – Umass India Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.com/# indian pharmacy online

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican mail order pharmacies – Unm Pharm

Online medicine order Umass India Pharm Umass India Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# cheapest online pharmacy india

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# Umass India Pharm

https://unmpharm.xyz/# finasteride mexico pharmacy

the canadian pharmacy: Nyu Pharm – pharmacy in canada

Unm Pharm buy kamagra oral jelly mexico Unm Pharm

http://nyupharm.com/# medication canadian pharmacy

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# world pharmacy india

Umass India Pharm: Umass India Pharm – Umass India Pharm

canadianpharmacyworld com: canada drug pharmacy – canadian online drugs

https://unmpharm.com/# Unm Pharm

top 10 online pharmacy in india: Umass India Pharm – top online pharmacy india

Unm Pharm: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – Unm Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.com/# world pharmacy india

canada drugs: canadian pharmacy world – the canadian pharmacy

best mexican online pharmacies: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

http://unmpharm.com/# amoxicillin mexico online pharmacy

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# buy prescription drugs from india

Umass India Pharm: Umass India Pharm – Umass India Pharm

http://umassindiapharm.com/# Umass India Pharm

best mexican online pharmacies: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.com/# indian pharmacies safe

canadian family pharmacy: Nyu Pharm – online canadian pharmacy review

https://nyupharm.xyz/# canadian drugstore online

https://umassindiapharm.com/# mail order pharmacy india

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# Umass India Pharm

mexican pharmaceuticals online: purple pharmacy mexico price list – medicine in mexico pharmacies

http://nyupharm.com/# online canadian pharmacy

Unm Pharm: Unm Pharm – Unm Pharm

https://unmpharm.xyz/# buy viagra from mexican pharmacy

http://nyupharm.com/# canadian drugs

online shopping pharmacy india Umass India Pharm Umass India Pharm

https://umassindiapharm.xyz/# Umass India Pharm

The beauty of Born of Trouble lies in its honesty. This raw and powerful story is now available as a pdf. Experience the unfiltered emotions and the stark realities of a life lived on the edge. It is a story that doesn’t shy away from the truth. https://bornoftroublepdf.site/ Free Pdf Books Download

http://nyupharm.com/# 77 canadian pharmacy

This novel is a profound look at the complexity of love and forgiveness. The story is both tragic and beautiful. To access this book, you can search for the Clap When You Land PDF. https://clapwhenyoulandpdf.site/ Clap When You Land Free Pdf

http://umassindiapharm.com/# Umass India Pharm

Get the Is This a Cry for Help PDF and enjoy the convenience of having your favorite book on your phone. This digital file is lightweight and perfect for reading in short bursts. Secure your copy now and never be without a good story again. https://isthisacryforhelppdf.site/ Is This A Cry For Help Archive.org

https://nyupharm.com/# canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore

Enjoy a book that brings characters to life. The Boyfriend Candidate PDF is available for immediate download. It features vivid and real personalities. Secure your ebook today and meet the people who make this story great. https://theboyfriendcandidatepdf.site/ The Boyfriend Candidate Epub Vk

перплекстти https://uniqueartworks.ru/perplexity-kupit.html

Experience the genius of Chuck Tingle. The Bury Your Gays PDF is pure genius. Don’t accept any substitutes. https://buryyourgayschucktinglepdf.site/ Bury Your Gays Chuck Tingle Supernatural

http://unmpharm.com/# buy viagra from mexican pharmacy

perplexity купить подписку на год https://uniqueartworks.ru/perplexity-kupit.html

Read, enjoy, and share the love. The Bury Your Gays PDF is meant to be shared. Spread the word and help bury the bad tropes for good. https://buryyourgayschucktinglepdf.site/ Bury Your Gays Pdf File

indian pharmacy Umass India Pharm Umass India Pharm

perplexity купить https://uniqueartworks.ru/perplexity-kupit.html

Has anybody tried safe Mexican pharmacies. I ran into a decent blog that ranks affordable options: п»їhttps://polkcity.us.com/# mexico pharmacy price list. Looks legit.

п»їRecently, I discovered an interesting report regarding buying affordable antibiotics. It explains WHO-GMP protocols when buying antibiotics. If you are looking for Trusted Indian sources, go here: п»їtop online pharmacy india. Cheers.

п»їJust now, I found an interesting resource concerning generic pills from India. It details how to save money when buying antibiotics. If anyone wants Trusted Indian sources, read this: п»їhttps://kisawyer.us.com/# Online medicine home delivery. It helped me.

Has anybody tried getting antibiotics without prescription. I discovered a good blog that lists best pharmacies: п»їhttps://polkcity.us.com/# mexico pharmacy online. Check it out.

perplexity как оплатить в россии https://uniqueartworks.ru/perplexity-kupit.html

Experience the ultimate horror satire. The Bury Your Gays PDF is the king. Long live the king. https://buryyourgayschucktinglepdf.site/ Chuck Tingle New Horror Novel Pdf

п»їTo be honest, I came across an interesting guide regarding ordering meds from India. The site discusses how to save money for ED medication. If anyone wants cheaper alternatives, check this out: п»їkisawyer.us.com. Good info.

Stop overpaying and save money on prescriptions, I recommend checking this resource. It reveals where to buy cheap. Discounted options available here: п»їhttps://polkcity.us.com/# online pharmacies in mexico.

п»їRecently, I stumbled upon a great page concerning cheap Indian generics. It explains CDSCO regulations for generic meds. For those interested in Trusted Indian sources, read this: п»їthis site. It helped me.

Stop overpaying and save cash on meds, I recommend visiting this archive. The site explains trusted Mexican pharmacies. Best prices found here: п»їpolkcity.us.com.

Just wanted to share, an important overview on FDA equivalent standards. The author describes quality control for antibiotics. You can read it here: п»їп»їclick here.

п»їJust now, I found a great page about buying affordable antibiotics. It details how to save money when buying antibiotics. For those interested in Trusted Indian sources, read this: п»їkisawyer.us.com. Worth a read.

I was wondering about ordering meds from Mexico. I found a cool post that compares affordable options: п»їpolkcity.us.com. Seems useful..

п»їTo be honest, I found a useful page regarding Indian Pharmacy exports. The site discusses CDSCO regulations for ED medication. In case you need cheaper alternatives, go here: п»їreading. Cheers.

п»їLately, I came across an interesting guide regarding cheap Indian generics. It covers WHO-GMP protocols for ED medication. For those interested in reliable shipping to USA, go here: п»їkisawyer.us.com. Cheers.

Heads up, a helpful overview on buying meds safely. It explains quality control for antibiotics. You can read it here: п»їhttps://polkcity.us.com/# mexican pharmacy menu.

Si buscas la manera perfecta de deshacerte de compromisos indeseados, este texto es tu mejor aliado, encuentra fórmulas de cortesía que funcionan como un escudo protector y aprende a mandar a la media cualquier situación que no te convenga. https://comomandaralamediadeformaeducadapdf.cyou/ Libro Como Mandar A La Mierda De Forma Educada

п»їActually, I stumbled upon a useful page concerning ordering meds from India. It explains the manufacturing standards for generic meds. For those interested in reliable shipping to USA, visit this link: п»їtop 10 pharmacies in india. Worth a read.

п»їLately, I discovered an informative resource regarding ordering meds from India. The site discusses the manufacturing standards on prescriptions. For those interested in factory prices, read this: п»їhttps://kisawyer.us.com/# reputable indian online pharmacy. Hope it helps.

La guía definitiva para amarte a ti mismo, aprende a respetarte y a mandar a la media la autocrítica feroz de forma educada, convirtiéndote en tu mejor amigo y aliado incondicional. https://comomandaralamediadeformaeducadapdf.cyou/ Como Mandar A La Mierda De Forma Educada Bolsillo

La teoría de Let Them ofrece una perspectiva refrescante sobre el control. Busca la edición en español y el formato PDF completo para profundizar. Al internalizar estos conceptos, te volverás inmune a las provocaciones y encontrarás una estabilidad emocional que te permitirá enfrentar cualquier reto con serenidad. https://lateorialetthem.top/ Let Them Theory Español Pdf Gratis

FYI, an official analysis on cross-border shipping rules. It breaks down pricing differences for antibiotics. Link: п»їUpstate Medical.

п»їJust now, I found an interesting report concerning ordering meds from India. It details how to save money for ED medication. For those interested in Trusted Indian sources, read this: п»їkisawyer.us.com. Might be useful.

Deja de ser la terapeuta de tu pareja y sé la tuya propia. Este libro te guía. Disponible en formato electrónico, es fácil de consultar. Retoma el control de tu energía y dirígela hacia tu propio crecimiento. https://lasmujeresqueamandemasiadopdf.cyou/ Libro Las Mujeres Que Aman Demasiado

Descubre cómo la simplicidad es la clave de la felicidad, baja el manual y aprende a despojarte de lo superfluo, mandando a la media el consumismo vacío de forma educada y valorando lo esencial. https://comomandaralamediadeformaeducadapdf.cyou/ Libro Como Mandar A La Mierda De Forma Educada

Just wanted to share, an official guide on cross-border shipping rules. The author describes how to avoid scams for generics. Source: п»їhttps://polkcity.us.com/# pharmacy online.

п»їRecently, I stumbled upon an informative page about buying affordable antibiotics. It covers the manufacturing standards when buying antibiotics. For those interested in cheaper alternatives, check this out: п»їreading. Might be useful.

Para quienes desean sanar sus relaciones y evitar conflictos innecesarios, estudiar la teoría de Let Them es un gran paso. Disponemos de información detallada en español, ideal para quienes buscan el texto completo. Descubre cómo esta mentalidad de desapego puede transformar tu ansiedad en calma y devolverte el control de tu vida. https://lateorialetthem.top/ La Teoria Let Them Libro Pdf

Descubre cómo la curiosidad vence al miedo, baja el manual y aprende a explorar lo nuevo y a mandar a la media los prejuicios de forma educada, abriendo tu mente a un mundo de posibilidades. https://comomandaralamediadeformaeducadapdf.cyou/ Como Mandar A La Mierda De Forma Educada. Pdf

No permitas que la obsesión controle tu vida. Este PDF es una herramienta de liberación. A través de sus capítulos, aprenderás a identificar las señales de alerta. Es una lectura obligatoria para quien desea dejar atrás el papel de víctima y empoderarse. https://lasmujeresqueamandemasiadopdf.cyou/ Autoayuda Mujeres Pdf

Create a lifestyle for a lean body. This resource focuses on habits. The metabolic freedom pdf is your handbook for metabolic freedom. https://metabolicfreedom.top/ Ben Azadi Metabolic Freedom Pdf

Si quieres dejar huella, aprende a tratar bien a la gente, descarga la guía y descubre cómo ser inolvidable, mandando a la media la mediocridad en el trato de forma educada y marcando la diferencia. https://comomandaralamediadeformaeducadapdf.cyou/ Como Mandar A La Mierda De Forma Educada .Pdf

Si buscas una transformación real, prueba la teoría de Let Them. El texto en español y completo es el primer paso. No es solo una teoría, es una práctica diaria que reconfigura tu cerebro para buscar la paz en lugar del conflicto y la aceptación en lugar de la resistencia. https://lateorialetthem.top/ La Teoría De Let Them En Español Pdf

¿Por qué atraes siempre el mismo tipo de pareja? Este PDF tiene la respuesta. Analiza tus patrones inconscientes con esta guía experta. Es el momento de romper el ciclo y abrirte a relaciones sanas y constructivas. https://lasmujeresqueamandemasiadopdf.cyou/ Frases Del Libro Las Mujeres Que Aman Demasiado

п»їActually, I stumbled upon an interesting article about ordering meds from Mexico. It explains the safety protocols for ED medication. In case you need reliable shipping to USA, take a look: п»їread more. Cheers.

Sunrise on the Reaping offers Suzanne Collins’ powerful exploration of trauma and survival. This PDF prequel follows sixteen-year-old Haymitch during the Quarter Quell. Discover why he became the cynical mentor Katniss knew. Get your free instant download without registration today. https://sunriseonthereapingpdf.top/ When Is Sunrise On The Reaping Movie Coming Out

Unchain Iron Flame’s story! Dragons, drama, devotion define Violet’s arc. Get free PDF at ironflamepdf.top today! https://ironflamepdf.top/ What Chapter Is The Throne Scene In Iron Flame